That I would have to come to Italy to be able to write about Indiana… says something deep and mysterious about proximity, separation, space to marinate. And the defects and peculiarities of this wandering scribbler.

For I realize, theoretically at least, that any distinct experience is far more than just a strand of unrelated events, connected solely because they occur in the timeline of a single person. Far more.

Still, the Indiana Homecoming was a dope slap.

Gentle — but a dope slap, all the same.

Headline: “JL is Not an Island.”

Subhead: “Duh.”

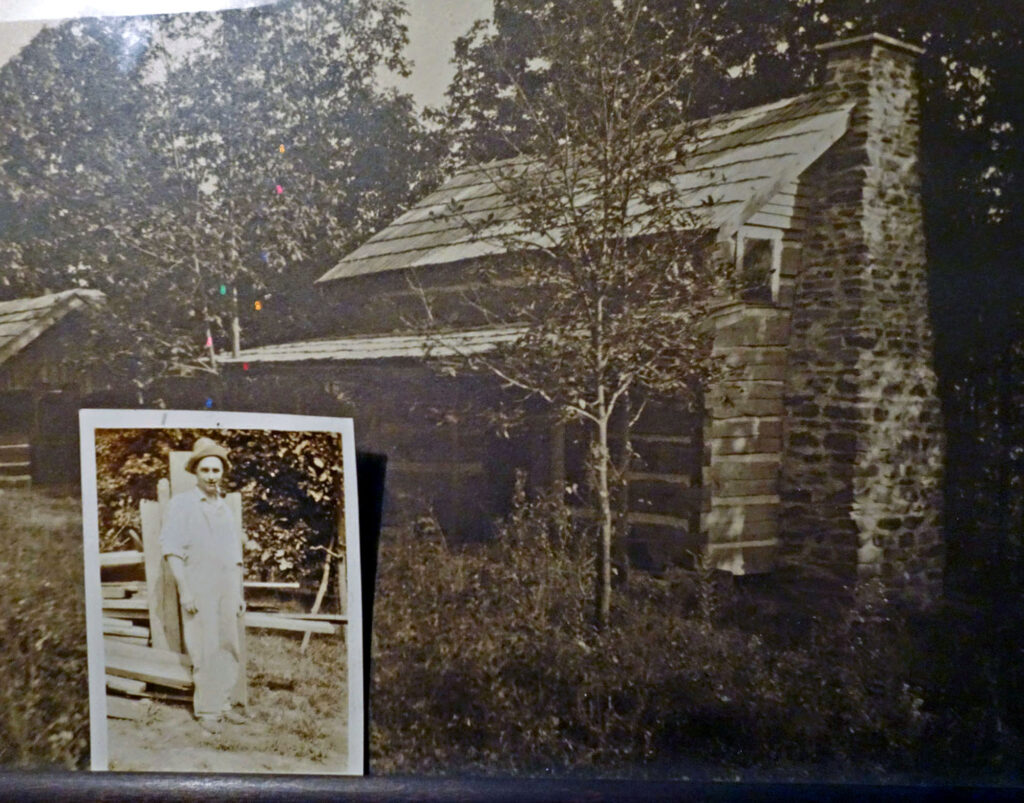

It took traveling 600-plus miles to a seventh generation family farm, now owned by cousin Tom Bennett, examining ancient graves in family cemeteries with names well known to me but never seen “written in stone,” reuniting with distant Indiana cousins, witnessing a treasure trove of precious paintings by an elderly maiden aunt, and sleuthing out a 1925 log cabin deep in the rolling wooded hills of Brown County — a cabin so like mine, yet to repeat for emphasis — it took all this and more… for me to get it. Humbled by the burst of insight/satori that I was NOT the first cabinman in the family — as I have so proudly bragged to myself. It’s all puffery. Charlie Rush beat me to chinking and chimney building by 50 years!

Seeing the happy Indianapolis house where my grandparents and their three girls lived, circa 1918-1928 — now lovingly restored by the gracious veterinarian couple of Carla and Todd Cloud., who welcomed drive-by inquisitors as if we were long-lost family…and driving by grandfather Rush’s massive public library in downtown Indianapolis helped me to embrace the man’s professional stature —a career that would eventually culminate with the head librarianship at UNC’s Wilson Library in Chapel Hill.

Then there were the long, gloves-off conversations with each of two first cousins, dear Sandy and Joy, hearing them tell family lies, stories, fables, legends — the likes of which I’d never heard before. We three, (Sandy, 84, living in Florida; and Joy, 78, in Wyoming), long lost but reunited now, began plotting this Hoosier homecoming/pilgrimage way last summer when I learned they’d never seen this sacred family place.

Let me be clear. When i say we three were “long lost,” the fault is entirely that of this scribbler who was raised in a dysfunctional and decidedly strange family — one which made little effort to stay in touch.

Snapshots from 1955

Rush Hill — an appellation in my childhood’s hard drive as magic as a family Hogwarts, as idyllic as a Camelot — thanks to a 1955 roadtrip from NC to the family farm in tiny Fairmount, where the grandparents took me at age 10 (while my older brother Nick, 15, was off at summer camp; his last summer).

Indeed, I have to thank Nick, whose brief life i have been trying to write about for these last 15 years, for inspiring this spring of 2022 pilgrimage. While researching Nick’s past, I stumbled across a trio of old photos from a dusty family photo album — three black-and-white snapshots of that Indiana homecoming 66 years ago.

There I am sitting on a fencepost looking for the world like a farm boy (not!). Then, there’s Grandad Rush seated on the porch showing me some book, which, by the furrowed brow on my forehead, hints that’s its a tough read. And finally, the family group shot, which I’m betting I took, since I’m not in the frame.

In front, are the farm kids, Sally, David and Tom. At far right is my Aunt Alison Roberts (Sandy’s mom). Behind her in back is big Joe Bennett, the farmer scion of Rush Hill. Beside him is Aunt Myra Baldwin; in the center is the merry farmwife Dorothy Bennett. Then at far left are Nick and my grandparents, Lionne and Charlie Rush.

Looking at these snapshots now, I’m moved by the realization that we are witnessing my beloved granddad, who was raised in this house — as what he called a “Thee and Thou Quaker,” making his final visit to his childhood home. Charles Everett Rush, 70 in these snaps, would die in January 1958, just a couple of years after these photographs were made. This was his “sentimental journey home,” his farewell tour. Perhaps that explains the sober look on his face. And Lionne’s uncharacteristically affectionate embrace.

Our Magic Man

Years ago as a visiting faculty fellow at National Geographic Magazine in D.C., I learned that the rock star photographers assigned to any foreign country were greatly aided by what was known at Nat Geo as a “magic man” or “fixer” — a bi-lingual savvy local who could smooth over the rough spots for the foreign photojournalist and make it all happen.

On our Hoosier homecoming, Tom Bennett was that magic man; our fixer.

Cousin Tom, the 79-year-old scion preferred to call the place “the Bennett Farm,” — and who can blame him, after two generations of Bennett blood sweat and tears.

Tom made the 168 acre farm viable by supplementing his income with a lifetime of public school teaching, not unlike his late dad Joe, who worked as a surveyor while he maintained the farm.

Prior to the trip, I had been advised that farmer Tom was something of a loveable curmudgeon. Of course, we got along famously.

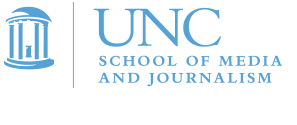

With the quiet pride of an art museum curator, Tom hauled out of storage a family legacy, a dozen or so paintings by my great aunt Olive Rush.

Olive Rush, the Hoosier Quaker farmgirl gone west in 1920, way ahead of her time, boldly helping launch the arts colony in Sante Fe, a colleague of August Baumann and Georgia O’Keefe, going on to relative fame painting murals for the WPA in post offices and hotels, teaching local Navajo kids to do their own artwork, finally claiming her own distinct artistic identity with her dreamy water colors, so like pre-historic cave drawings or Zen/Chinese ink drawings. This older sister of my beloved grandfather Charlie — am I not also of her DNA? So it would seem.

Bennett Farm/Rush Hill

And at 76, I loved the old farmhouse at Rush Hill just as much, if not more, than i did at 10. The house itself, perched on its little knoll, surveying the flat flat flat corn and soybean fields below, has aged noticeably, in contrast to Olive Rush’s iconic watercolors from the ’30s that paint it in a better light. The big house has not fallen into disrepair — no, that would be too harsh a description, but she could stand some cheering up.

To her credit, built by my ancestors in 1853-’55, this no-frills working farmhouse supported and sent forth seven generations of not just farmers but also ministers, teachers, professors, surveyors, journalists, snapshooters, librarians — and of course, artists. If Rush Hill has the feel of a family museum, that’s not such a bad thing, is it?

To be clear, Rush Hill is not run down. More like weary from a long and productive life. And who can fault a 170-year-old midwestern working farmhouse for presenting such an honest face. She is like a once lovely young woman, now aged and lined and a little stooped, but still beautiful in a wise and well lived in sort of way.

The house reminds me of the old lady who objected to Henri Cartier-Bresson making her portrait because she thought she had too many wrinkles — to which the venerable French photographer responded convincingly, “Oh! It’s the wrinkles after all, that make a face interesting; after a while you get the face you deserve.”

So please, no bump outs, no hot tub additions, no great room renovations, no fancy-schmanzy kitchen do-over, no face lifts.

Rush Hill is perfect. Just the way she is.

Epilogue

That this scribbler is a bookish, log cabiny, artsy, academic, newspapery dude is almost preordained. Percolating on the experience forces this would-be loner to confront the fact that he is — and has been all along — a part of a system, a family. My god, I’m a Rushie through and through, stem to stern. The pre-supposed title of “self-made man” I previously crowned myself with, well — it’s a total self-aggrandizing myth.

Welcome home, Mr. Rush.