Jock Lauterer, Senior Lecturer and Director of the Carolina Community Media Project at the School of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, has returned to China for a third summer to teach Community Journalism at workshops from Beijing to Chongqing to Guangzhou. His latest book, “Community Journalism: Relentlessly Local,” was released on May 28 in Shenzhen, after being revised and translated into Mandarin Chinese. Because of the difficulty of pronouncing the name “Jock,” our man in China was often introduced as “Mr. Joke.”

Of all the encounters I have been privileged to experience in China, my very favorite has been with Li GuoChen, or simply Editor Li — my “brother from another mother” in the city of Foshan in the southern province of Guangdong.

“Older Brother Joke,” he calls me.

We met last year at a community journalism conference in the city of Hefei, and the connection was instant and mutual. A tall lanky man of constant motion, salt-and-pepper black hair and a set of merry eyes — Li is fiercely enthusiastic about local newspapering, won’t take no for an answer, and is a man after my own heart.

His English is halting; my Chinese is non-existent. Yet we communicate. I feel like Kevin Costner in “Dances with Wolves,” struggling to communicate with his new Lakota Indian friends, Kicking Bird or Wind in His Hair — we get very close, lock eyes, wave our hands and find one common word we can both understand — then, “Ah! Ah! Ah!” Li cries in delight, when he gets it.

With his irrepressible good cheer, boundless energy, and utter sincerity, Editor Li is not to be denied. No wonder his eight community newspaper start-ups have been so successful. He gets it: community journalism is all about social capital and relationship building and maintenance.

I think to myself, Editor Li would be fun to work for – fun to work WITH.

In fact, that just might happen.

He has a vision of creating the first-ever Chinese academic program in Community Journalism at his local university, and appears to have the support of the academic leaders at Foshan University.

On the way to one a town-hall style meeting with readers, he turns from the steering wheel and challenges, “Want to join me!?” Almost driving off the road with childish excitement. Only a fool would refuse my irrepressible younger Chinese brother.

IN THE TRENCHES

When we walk into the room at the Luo Cun Community Newspaper, a crowd of about 30 elderly readers leap to their feet and began applauding, hands held over their heads to clap. (Now, when’s the last time I saw a newspaper publisher get that kind of reception?)

But Editor Li is not there to accept their adulation. He introduces me as “the godfather of Chinese community journalism.”

Can I put that on my vita?

He’s there to get feedback about the new community weekly he started earlier this year. The seniors are led by a Mr. Zhou, a 60-something articulate retiree, who tells us, that prior to the new newspaper, the neighborhood had felt ignored.

“Your newspaper is a pioneer, and gives us a voice,” he says. And he requests help from the paper in organizing more activities for the seniors…some sort of a dance club or sports team, he suggests.

“I will find the money for you!” Editor Li responds. “You organize it, and we’ll help.” And he continues, “We should put all our resources together to make you happier to live in this community. If you have good ideas, maybe we can publish it in the newspaper, and other people will want to help.”

Little wonder Ed. Li’s paper is so popular. Mr. Zhou praises the young women reporters: “They work a lot in the community. They dig out the news. They make friend with the seniors. They are not arrogant. When they see me, they say things like ‘Hello, Uncle Zhou!’”

Then Mr. Zhou says the most remarkable thing: “The best thing about this community newspaper is that you can constructively criticize the government. The party newspaper — it’s a mouthpiece, and we don’t care about it. But we like this newspaper because it talks about us! We read every page!”

Asked to give a specific example of how the newspaper had helped, Mr. Zhaou recalls how he had complained to the local government about a huge pothole in the road. Nothing happened. After two to three months with no response, he gave up and called the paper. Within two days of the story’s publication, the pothole was fixed.

And here’s the really good thing: Prof Chen Kai explains that in the more progressive and liberal southern province of Guangdong, “local government here is not offended when the newspaper is critical.”

Ed Li is pleased. “I want to use my heart to do something useful for the citizens, to help resolve some of their problems….that’s my slogan.”

We hear the same themes at a visit to a second start-up of 2014, the Qiao Shan News, where the local government leader, introduced to me as “Mr. Dragon,” says local government donated office space so that “citizens can come talk with journalists…to help collect residents’ demands, because the government has to listen to the concerns of the citizens, and that makes the government more effective when it makes decisions.”

I’m starting to get it now. Under the Chinese system, the ponderous multi-leveled local governmental bureaucracy gets in the way of documenting feedback from just plain folks.

“The community newspaper serves as a conduit for collecting public opinion,” Mr. Dragon tells me, and this is a very important and valuable function.

Disgruntled citizens can even talk to reporters about “sensitive issues…that might be too sensitive to be published,” — the American equivalent of “deep background,” which, though “off the record,” still needs to be passed on and documented.

Editor Li agrees. “We want the newspaper to be a bridge between the citizens and the government.”

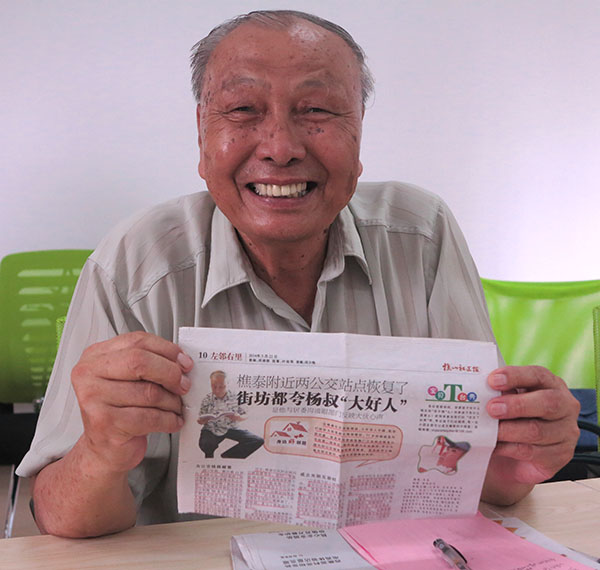

We meet Mr. Yang, a 77-year-old former government worker, who serves as a “citizen journalist” for the paper — as a trusted source and tipster. After he complained to the paper about the lack of bus stops in Qiao Shan, two more bus stops were added.

*** *** ***

Later that day, we are joined at Starbucks by Tang Wan, a 42-year-old editor- in-chief of Editor Li’s group of eight papers. Before joining Editor Li’s team, she’d worked for years on the big metro dailies; she likes community journalism better, she tells us. And, most importantly, she buys into Li’s vision for the future of journalism in China.

“We feel as if Editor Li can see into the future,” she tell us over cappuccino, “This is the appropriate time to introduce Community Journalism into our society…though our papers are small in size, they are not at all small in their influence in their communities.”

To be sure, these Chinese newspapers get their start-up and some operating capital from the government, a fact of life here that wouldn’t fly in the good old U.S. of A. Be that as it may, after three years of marginal success, last year Li’s papers began raking in serious local advertising dollars – good old fashioned capitalism. The newspapers, (tabloid, 16 pages, free weekly, average circulation of 50k) are “100 percent local and very profitable.”

When I asked her if she sees Ed. Li as a pathfinder, she demurred, “Ask him yourself.”

So I did. And Li, ever the humble Chinese, said this: “We are confident in our strengths; but we will never name ourselves as the leader.”

Prof. Chen Kai was more forthright: “He sets a good example for what Chinese Community Journalism should be. Your first priority is to serve your community. And THEN money will come. You have to be patient!”

*** *** ***

At the end of the day, I’m thinking, so here’s a publisher who puts people first and profits second. Here’s a publisher who wants to serve the greater good. Yes, he does work with and takes money from the government, after having convincing them of the value of community journalism Does that make him a lapdog?

Me, the hard-core First Amendment wonk, is thinking: This ain’t exactly watchdog journalism. But, as I am repeatedly told, “This is China!” So this is progress. I keep going back to the rhetorical question posed by my lifelong buddy and journalism professor, Steven Knowlton of Dublin City University. And Prof. Knowlton is speaking specifically of China here when he ponders: “How do you do good journalism if you don’t have a free press? The answer, of course, is, eventually, Community Journalism.”

My 15 seconds of fame: ‘Ta-Da!” in Chinese

In a large convention hall are seated about 125 Chinese reporters, photographers, ad people, editors and newspaper directors (the latter being the equivalent of our publishers).

They are from all across China — from Beijing in the north, from Hefei in the east and Chongqing in the far southwest to Shenzhen in the far south, where we are now.

They have come here to this community journalism conference (sponsored by the Southern Metro Daily of Guangdong) to share their best practices and learn from others — and to celebrate the dynamic growth of community journalism in China, a relatively new media phenomenon here. “It’s still very primitive,” says one publisher.

At each place setting, a copy of my just-off-the-presses book rests on dark green velvet. Each conference-goer gets a free copy, and before the speechifying begins, I am besieged by journalists humbly seeking my signature — a moment for any author to treasure, no matter how many times it happens.

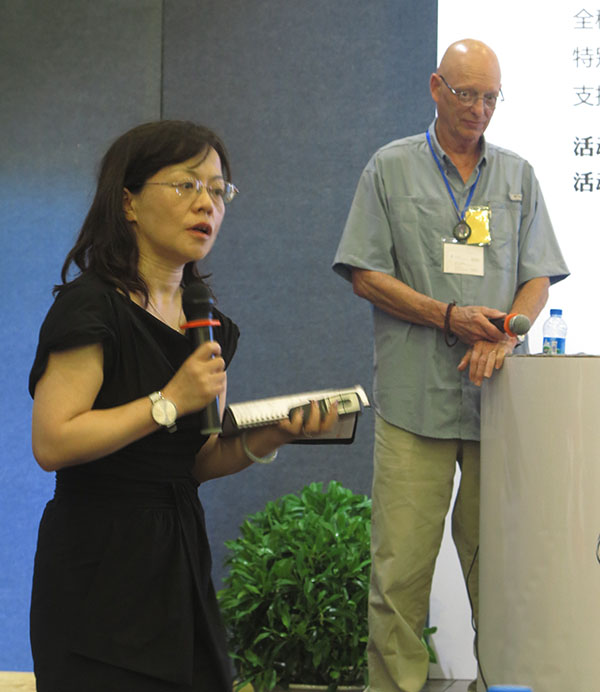

Then, when our time comes, Prof. Chen Kai and I do our best program, playing tag-team with translations in front of a jumbo-tron — very high tech and state-of-the-art, the likes of which this ink-dabbler has never seen. Our PowerPoint looked to be the size of a basketball court.

My favorite part of this convention: as each speaker is being introduced, and then walks to the podium, the PA system blasts martial music, what can only be called epic heroic, reminding me of the Olympic-style John Williams fanfare…so that you arrive at the podium to give your little speech feeling like you’ve just won gold!

I might copy that theme music and use it for my entrance into my classes back at UNC.